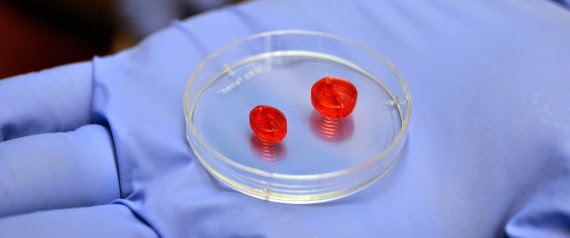

Ultimately, the goal is to create a new heart for a patient with their own cells that could be transplanted. It is an ambitious project to first, make a heart and then get it to work in a patient, and it could be years — perhaps decades — before a 3-D printed heart would ever be put in a person. The technology, though, is not all that futuristic: Researchers have already used 3-D printers to make splints, valves, and even a human ear. So far, the University of Louisville team has printed human heart valves and small veins with cells, and they can construct some other parts with other methods, said Stuart Williams, a cell biologist leading the project. They have also successfully tested the tiny blood vessels in mice and other small animals, he said. Williams believes they can print parts and assemble an entire heart in three to five years. The finished product would be called the “bioficial heart” — a blend of natural and artificial. The biggest challenge is to get the cells to work together as they do in a normal heart, said Williams, who heads the project at the Cardiovascular Innovation Institute, a partnership between the university and Jewish Hospital in Louisville. An organ built from a patient’s cells could solve the rejection problem some patients have with donor organs or an artificial heart, and it could eliminate the need for anti-rejection drugs, Williams said. If everything goes according to plan, Williams said the heart might be tested in humans in less than a decade. The first patients would most likely be those with failing hearts who are not candidates for artificial hearts, including children whose chests are too small for an artificial heart. Hospitals in Louisville have a history of artificial heart achievements. The second successful U.S. surgery of an artificial heart, the Jarvik 7, was implanted in Louisville in the mid-1980s. Doctors from the University of Louisville implanted the first self-contained artificial heart, the AbioCor, in 2001. That patient, Robert L. Tools, lived for 151 days with the titanium and plastic pump. Williams said the heart he envisions would be built from cells taken from the patient’s fat. But plenty of difficulties remain, including understanding how to keep manufactured tissue alive after it is printed. The 3-D printing approach is not the only strategy researchers are investigating to build a heart out of a patient’s own cells. Elsewhere, scientists are exploring the idea of putting the cells into a mold. In experiments, scientists have made rodent hearts that beat in the laboratory. Some simple body parts made using this method have already been implanted in people, including bladders and windpipes. The 3-D printer works in much the same way an inkjet printer does, with a needle that squirts material in a predetermined pattern. The cells would be purified in a machine, and then printing would begin in sections, using a computer model to build the heart layer by layer. Williams’ printer uses a mixture of a gel and living cells to gradually build the shape. Eventually, the cells would grow together to form the tissue. The technology has already helped in other areas of medicine, including creating sure-fitting prosthetics and a splint that was printed to keep a sick child’s airway open. Doctors at Cornell University used a 3-D printer last year to create an ear with living cells. “We’re experiencing an exponential explosion with the technology,” said Michael Golway, president of Louisville-based Advanced Solutions Inc., which built a printer being used by Williams’ team.