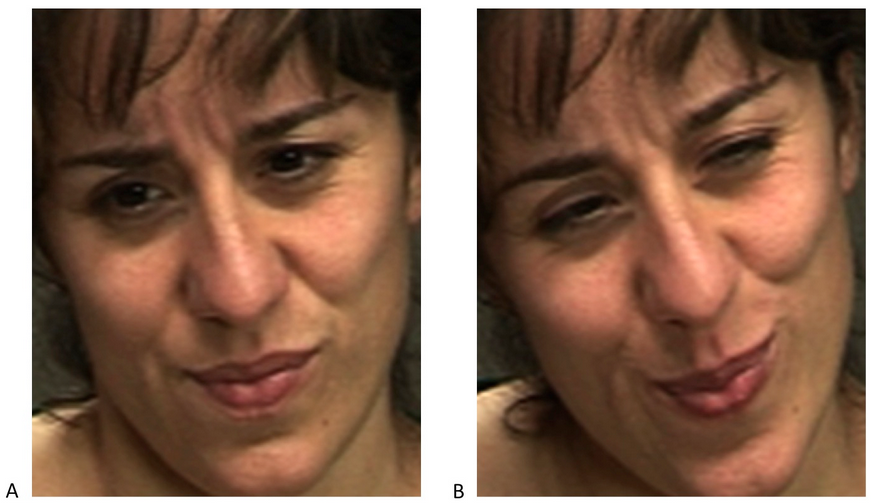

a smile, anger, sadness? A team of scientists says you’re probably just a good guesser. “In highly social species such as humans, faces have evolved to convey rich information, including expressions of emotion and pain,” says Kang Lee, of the University of Toronto. “And, because of the way our brains are built, people can simulate emotions they’re not actually experiencing — so successfully that they fool other people.” But it’s much harder to fool a new computer system developed by Lee and her colleagues. In a paper published today in Current Biology, they say the computer can see right through faked expressions of pain with 85 percent accuracy. Mere humans, on the other hand, may as well have been flipping a coin. Even after test subjects were trained to spot fake facial expressions, they were still only accurate 55 percent of the time. To generate real pain, people were made to hold their arms in ice water for one minute. It appears that no two sincere pain expressions are exactly alike because there’s not a muscle or muscle group responsible for wincing, according to the researchers in a news release announcing the findings. Consequently, there’s no telltale sign to watch out for. Instead, they say, it has to do with the “dynamics” of spontaneous vs. a deliberate motion. “The computer is much better at spotting the subtle differences between involuntary and voluntary facial movements,” says Lee, who also worked with Marian Bartlett, of the University of California, San Diego. Where do you look to spot these dynamics? The mouth. “Fakers’ mouths open with less variation and too regularly,” they say. But good luck spotting that. Computer vision, however, can be programmed to do all sorts of things. They’re experts at unbiased pattern recognition. And that’s where the array of applications comes in, some of which seem creepy in a Minority Report sort of way. “Our computer-vision system can be applied to detect states in which the human face may provide important clues as to health, physiology, emotion, or thought, such as drivers’ expressions of sleepiness, students’ expressions of attention and comprehension of lectures, or responses to treatment of affective disorders,” Bartlett says. They say their technology could be applied to “homeland security, psychopathology, job screening, medicine, and law.” Before anybody gets too excited, we just hope they keep in mind the computer was wrong 15 percent of the time.